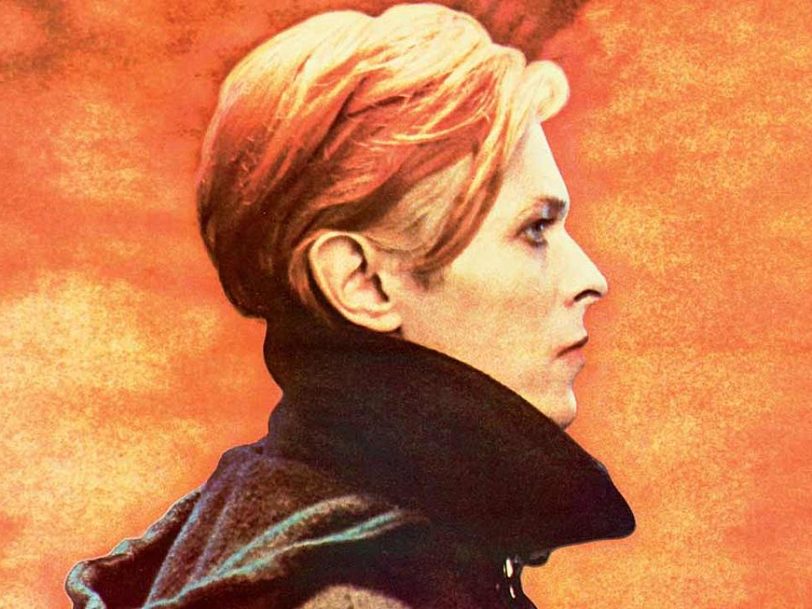

The first instalment of his highly acclaimed “Berlin Trilogy”, David Bowie’s Low album retains an otherworldliness which still fascinates today. A critical touchstone since its initial release, on 14 January 1977, Low is widely lauded for blueprinting what we now refer to as “post-punk”, but it’s not overly dramatic to suggest that it also saved Bowie’s life.

“I wouldn’t have survived the 70s”

“I was in serious public decline, emotionally and socially,” Bowie told The Telegraph in 1996. “I think I was very much on course to be another rock casualty. In fact, I’m quite certain I wouldn’t have survived the 70s if I’d carried on doing what I was doing. But I was lucky enough to know somewhere within me that I was really killing myself, and I had to do something drastic to pull myself out of that.”

The “decline” Bowie referred to was the cocaine dependency and high-profile celebrity lifestyle that had started to consume him while he was based in Los Angeles during the mid-70s. Though also a time of great artistic worth (it yielded the seminal albums Young Americans and Station To Station, not to mention his starring role in Nicolas Roeg’s iconic sci-fi drama, The Man Who Fell To Earth), it left Bowie “at the end of my tether physically and emotionally”, and with the belief it was necessary to relocate simply to survive.

“I can hear myself struggling to get well”

Along with his friend and former Stooges frontman Iggy Pop, Bowie made his break following his Isolar – 1976 Tour, moving first to Switzerland and then to West Berlin late in in the year. Though both men wished to pursue healthier lifestyles, Bowie also decided on Germany for aesthetic reasons. While making Station To Station, he’d tuned into the music of envelope-pushing German outfits such as Neu!, Harmonia and Kraftwerk – in particular, the latter’s Radio-Activity album.

“What I was passionate about in relation to Kraftwerk was their singular determination,” Bowie explained to Uncut in 2001. “They stood apart from the stereotypical American chord sequences and their wholehearted embrace of a European sensibility displayed through their music.”

Keen to incorporate a similar minimalism into his own sound, Bowie turned to former Roxy Music mainstay Brian Eno. Bowie was struck by the blend of art-rock and ambient music on Eno’s recent solo album, Another Green World, and he believed Eno could help him realise the “expressionist mood pieces” he was working on for his next record.

The union Bowie forged with Eno and producer Tony Visconti became the creative core behind Bowie’s next three studio albums, Low, “Heroes” and Lodger. However, while this seminal trio are uniformly referred to as Bowie’s “Berlin Trilogy”, much of Low was actually recorded at the Château d’Hérouville, outside of Paris. Bowie had previously recorded 1973’s Pin-Ups there and, in addition to Low, he also produced much of Iggy Pop’s solo debut, The Idiot, at the Château, before both albums were completed at Hansa Studios, close to the notorious Berlin Wall.

“I get a sense of optimism through the despair”

Low was similar in execution to Another Green World in that it proffered a heady mix of brittle, angular pop songs and haunting instrumental tracks. Featuring contributions from Bowie regulars such as guitarist Carlos Alomar, bassist George Murray and drummer Dennis Davis, the angular songs dominated the album’s first half. Visconti’s futuristic production gave them a harsh, metallic sheen, while most of Bowie’s lyrics were autobiographical, and the sense of fragility and isolation he invested in lines such as “Sometimes you get so lonely/Sometimes you get nowhere” (Be My Wife) and “Pale blinds drawn all day/Nothing to do, nothing to say” (Sound And Vision) offered insights into his state of mind as he embraced his newfound sobriety.