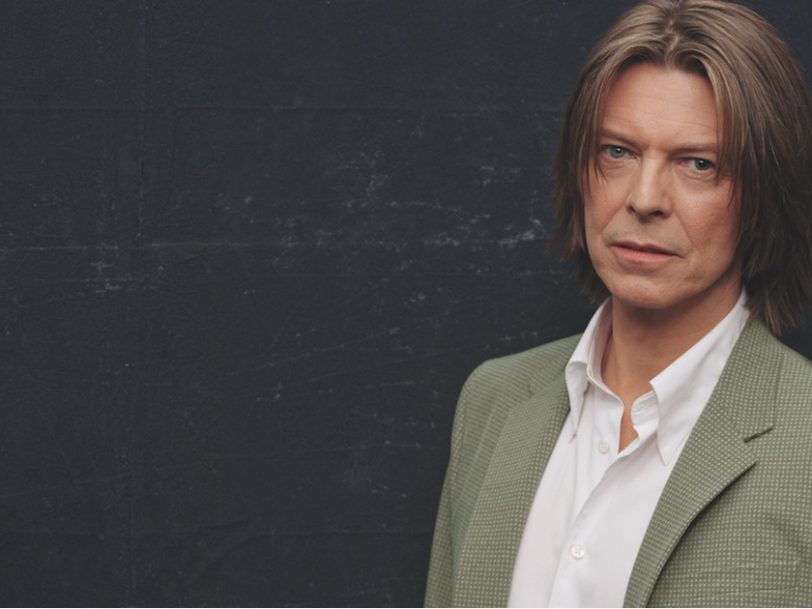

To the outsider, the ever-forward-thinking David Bowie may have seemed in an unusually reflective state of mind as he entered the 2000s. His final album of the previous decade, 1999’s ‘hours…’, often took a contemplative tone, while his headlining slot at Glastonbury 2000 was a gleefully hits-based affair that acted as a victory lap for an artist who was often too busy shaping his future to acknowledge his past. While running his band through rehearsals for a setlist that included such vintage classics as Changes, Life On Mars?, “Heroes” and Let’s Dance, however, Bowie began to reach even further back into his seemingly endless list of songs. Dusting off a swath of pre-fame tunes originally recorded in the mid-to-late 60s – some of which he hadn’t even released at the time – Bowie decided to re-record them with his new band for an album he planned to call Toy, but which was shelved almost as quickly as it was made.

“It was interesting to go from Earthling to Toy,” Bowie’s then bandleader, Mark Plati, tells Dig! Plati’s engineering and synth programming on the former album had helped Bowie realise his experiments in drum’n’bass in 1997, but during the Toy sessions he found himself at the helm of a more traditional live-in-the-studio set-up. “On one level, it made total sense, because it was David,” he says. “It wouldn’t have made sense for anyone else. But because it was him, it was like, ‘OK, we’re doing this today. Sure.’”

Listen to ‘Toy’ here.

“He would poke fun at the lyrics… It was really fun to do”

The seeds for Toy had been sown in August 1999, when Bowie recorded a session for VH1 Storytellers, including in the setlist his 1965 single Can’t Help Thinking About Me – a mod-era pop tune originally credited to David Bowie With The Lower Third. “He just liked doing it,” Plati says of the surprise choice. “It’s funny, he would poke fun at the lyrics on stage.” Buoyed with enthusiasm for the seemingly long-forgotten song, “This idea sprung: ‘Hey, let’s do some more of those tunes and see what it’s like.”

Across several sittings with Plati, and sometimes joined by his lynchpin bassist, Gail Ann Dorsey, Bowie began to pick contemporaneous songs that could conceivably fit together on an album, revisiting his own 60s tunes in the same way that he had used his 1973 Pin Ups album to pay homage to the songs that had most influenced him from the era. “We went through a lot of them and decided, ‘Well, that one’s cool. We like that one.’ Like you would for any album,” Plati recalls.

“It wasn’t a stated objective that we were going to do all this material as a way of being reflective,” he adds. “It was just really fun to do them that far down the road – especially in the position that he was in at that point. And it turned out to be, ‘Wow. With this band, and at this time’ – we enjoyed doing it.”