These days, most people can predict what the average punk retrospective will tell them before they’ve even read the contents. Almost inevitably, it’ll single out Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols, The Clash’s self-titled debut and Ramones’ Rocket To Russia as the Class Of ’77’s most necessary releases, though it might offer bouquets to boundary pushers such as Television’s Marquee Moon, Wire’s Pink Flag and Talking Heads’ Talking Heads: 77 if it’s a little more enlightened. Yet there’s another influential punk-era title which deserves equal billing, and that’s The Stranglers’ monolithic debut album, Rattus Norvegicus.

Listen to ‘Rattus Norvegicus’ here.

“Were we punk? Could I give a fuck?”

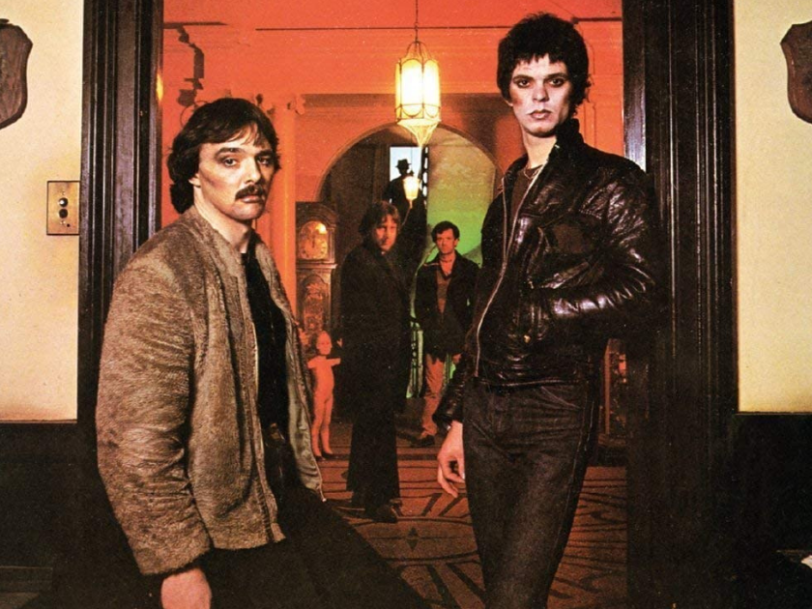

To temper that argument a little, The Stranglers’ relationship with punk has often been as fractious as the atmosphere at some of their early gigs. The Surrey quartet adopted a controversial name, and their early records had a suitably aggressive edge, but they openly flaunted their musical virtuosity and, as their median age was 28 in 1977, they were spurned by their peers for being too old. But then the band’s own attitude to punk was ambivalent at best. Channel 4’s Top Ten Punk programme once asked Stranglers bassist/vocalist Jean-Jacques Burnel about this, and he famously responded: “Were we punk? Could I give a fuck?”

One punk tenet The Stranglers could more willingly identify with, though, was the movement’s desire to celebrate the underdog. Indeed, you could argue that the band had adopted punk’s outsider-artist status long before Sex Pistols and The Clash had even set foot on a stage. Officially becoming The Stranglers during the autumn of 1974, the group initially endured a hand-to-mouth existence, falling back on vast reserves of self-belief to sustain themselves over the next two years.

“We had absurd amounts of self-confidence,” drummer Jet Black recalled in the sleevenotes for the 2018 reissue of Rattus Norvegicus. “Too much, in fact. But there was always some doubt in our minds that we could get signed, although there was no way we would admit it and there was no way we were going to give up. Historically, it was a two- or three-year period, but when you’re going through it and you’re starving and can’t pay the bills, it’s heavy.”

Born Brian John Duffy, the imposing, bearded Black was also a successful local entrepreneur who owned an off licence and a fleet of ice cream vans in the Guildford area of Surrey. He was already in his mid-30s when The Stranglers got off the ground, but if he wasn’t obvious rock-star material, then his bandmates were equally disparate.

“The Stranglers were different because they were darker and more twisted”

Prior to co-founding The Stranglers with Black, guitarist and vocalist Hugh Cornwell had spent time as a biochemistry graduate at Lund University, in Sweden. Anglo-French bassist Jean-Jacques Burnel, meanwhile, had a grounding in classical guitar, but he hadn’t considered a full-time career in music until he stopped to give one of Jet Black’s associates a lift and met his future bandmates at Black’s off licence. The last Strangler to enlist, Brighton-born keyboard whizz Dave Greenfield, came to the band through an advert in UK rock weekly Melody Maker, during the early summer of 1975.

Greenfield’s daring psychedelic Hammond organ skills and Moog synthesiser textures added the X factor to the already intriguing sounds his colleagues were throwing into The Stranglers’ melting pot. Cornwell’s rapier wit, sneering vocals and minimal, choppy guitar style set him apart as an ideal proto-punk frontman, while Burnel’s driving, yet infinitely melodic basslines provided the perfect foil for Black’s, hypnotic, no-frills drumming.