In a 2017 article in The Guardian, Creation Records founder Alan McGee suggested Echo And The Bunnymen were “the bridesmaids of rock” – the implication being that the band’s music never quite attained earned them a global profile or sales figures comparable to that of their peers such as U2 or Simple Minds.

On a purely commercial level, that argument may have legs, but judged on their artistic achievements and influence on successive generations of alt-rock stars, then this singular Liverpudlian group have long since knocked their contemporaries out of the park. Besides, they had their own take on what constitutes “success” all along.

Listen to the best of Echo And The Bunnymen here.

“The Bunnymen, more than any other group, more than R.E.M., more than U2, did try to discover our own voyage without destination,” the band’s frontman, Ian McCulloch, told The Washington Post in 2001. “We never had any goals particularly, other than to be seen as the coolest and the best, and the group that never sold out.”

McCulloch has never been backwards in coming forwards when it comes to doling out quotable remarks – and he’d been telling the media The Bunnymen were the best rock’n’roll band in the world years before Oasis’ Gallagher brothers turned self-aggrandisement into an art form. Yet The Bunnymen’s music really is hung with jewels, and the best Echo And The Bunnymen songs suggest their singer’s claims may not have been so outlandish after all.

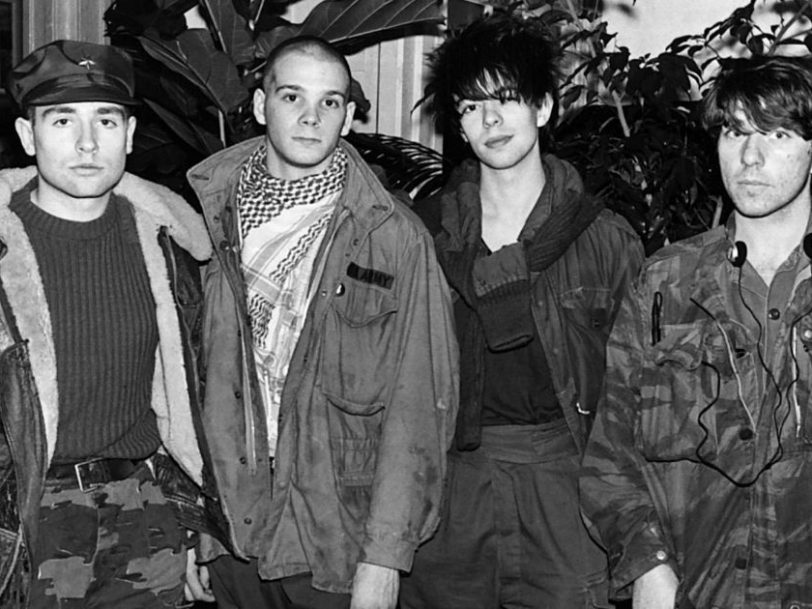

“Me and Will were always the chief ingredients”: forming the band

The Bunnymen’s voyage to becoming “the coolest and the best” had disarmingly humble beginnings. The fledgling group made their spontaneous live debut supporting their contemporaries The Teardrop Explodes at esteemed Liverpool punk haunt Eric’s in November 1978 – the place where guitarist Will Sergeant first encountered Ian McCulloch.

Sergeant knew of McCulloch from Liverpool’s nascent punk scene; the singer had briefly been involved in a formative but semi-legendary band, The Crucial Three, with fellow future Liverpudlian legends Julian Cope of The Teardrop Explodes and Pete Wylie of Wah! Sergeant and McCulloch also shared a love of David Bowie’s music, but the guitarist was going on instinct rather than prior knowledge of McCulloch’s musical capabilities.

Sergeant’s first impressions were that McCulloch “was quick, that he was funny, a similar sense of humour in a way”, he told the Scottish Herald in 2021, adding, “I thought he was great.”

The guitarist also discovered Mac was “a really good rhythm guitarist” himself during putative early sessions when the two spent hours playing guitar in the back room of Will’s father’s house in Melling, outside Liverpool. Listening to records by bands such as The Velvet Underground and The Doors, the pair would jam for hours on end in search of their own sound.

“Me and Will were always the chief ingredients,” McCulloch told The Washington Post. “And also we were the original two members. It was me, Will and a drum machine. He had a homemade guitar and a really damp house that he used to live in with his dad. So it was me, Will and a lot of condensation.”

“It was fantastic and such a rush”

Sergeant didn’t even know for sure whether McCulloch could sing before the band made their live debut at Eric’s. In typical punk DIY fashion, the band had acquired their third member, bassist Les Pattinson, just days before the show – and Pattinson had never previously played his instrument, either.

“I bought a Grant bass from [local friend] Robbie the punk for £40,” the bassist told Penny Black Music in 2011. “We rehearsed in NVCQ, a local art centre. Mac didn’t even turn up! Paul Simpson [of The Teardrop Explodes] was there and played keyboards. It was the first time I had played bass, and we came up with a song called Monkeys. Mac would later sing it at the first show, reading lines from a notepad. It could have gone so wrong, but it was fantastic and such a rush.”