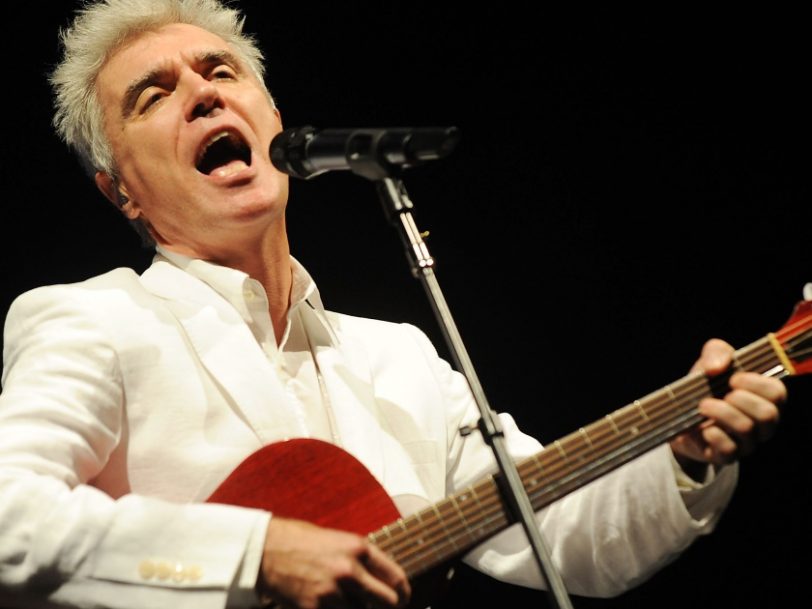

By the time he released his seventh solo album, Grown Backwards, David Byrne’s fans had been primed to expect the unexpected from the former Talking Heads frontman. Since his influential group disbanded, Byrne had released solo albums that explored South American music, created soundscapes for dance productions, launched a record label specialising in unsung music from the far reaches of the globe (Luaka Bop) and released a book of photography (1995’s Strange Ritual). And that’s just for starters. His 2002 worldwide hit single, Lazy – a collaboration with British electronic duo X-Press 2 – might have insisted that a laidback lifestyle came easy to him, but clearly that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Listen to ‘Grown Backwards’ here.

“I could indulge my recent love of melody”

Released on 16 March 2004, Grown Backwards was yet another rewarding sidestep. Rhythm had been a constant source of inspiration for Byrne – experiments with funk and disco had fuelled Talking Heads’ most forward-thinking and rewarding work, and Byrne’s first solo album proper, 1989’s Rei Momo, was a feast of Latin percussion. On Grown Backwards, however, rhythm took on a bit-part role; the tone here was stately and elegiac, with Byrne even tackling two operatic arias.

In the past, Byrne had turned the idea of songwriting on its head, using the grooves and mistakes that come with improvisation as a starting point. Grown Backwards, however, was rooted in a love of songcraft, as Byrne began with the tunes, humming melodies into a Dictaphone as they came to him and later building songs around them. He discussed the process with author Dave Eggers in an interview for The Believer: “Sometimes the writing and recording method becomes the unifying factor – the music on Remain In Light was written in the studio, layered one track at a time – on this one I knew in advance the make-up of the band, and… that I could indulge my recent love of melody.”

Going through a pile of micro-cassettes he had collected over the previous couple of years, Byrne began working “top-down, giving primacy to the melody, as the historical European music has usually done – Western Imperialist Music and all that implies”. The result was one of the most richly melodic and emotionally engaging collections of Byrne’s career.

Creating something accessible from disparate styles

Glass, Concrete & Stone is a stirring opener, with Byrne’s vocal underpinned by an inventive blend of cello and subtle electronic percussion. The orchestration is ramped up further on the following The Man Who Loved Beer, a cover of a Lambchop song, from their 1995 album, How I Quit Smoking. Where Lambchop’s original is draped with slow-moving, lush strings, Byrne employs choppy and dynamic string sections that propel the song forward with real urgency, creating a counterpoint to his measured delivery.