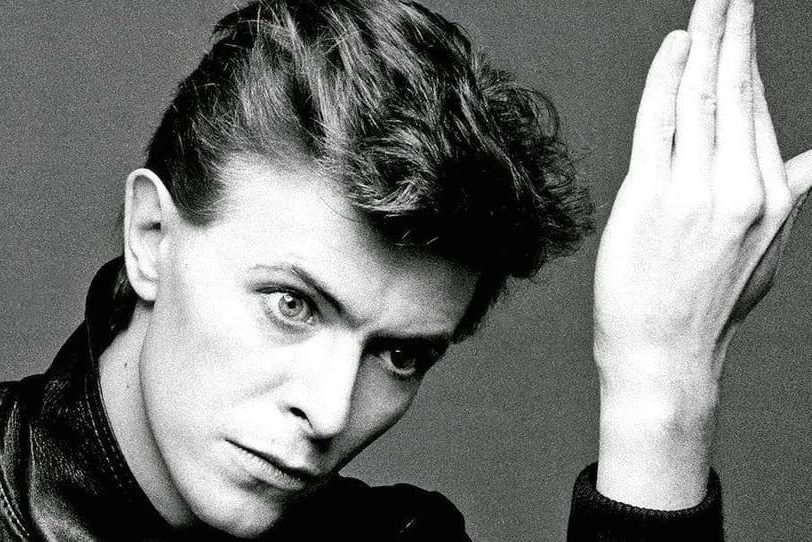

In the decades since it was recorded, in Hansa Tonstudio, in Berlin, David Bowie’s song “Heroes” has become embraced as a euphoric anthem for any grand occasion. And yet, as originally written, it was less optimistic in tone. “They use ‘Heroes’ for every heroic event,” producer Tony Visconti once noted, “although it’s a song about alcoholics.” However, underneath the layers of sound used to craft this uniquely affecting song, listeners have probed for their own interpretations of lyrics which had Bowie himself admitting, in 1990, “I’m not sure what that song means any more, which is kind of exciting.”

Listen to the best of David Bowie here.

“It sounded great. Why fix it?”

Lending its name to David Bowie’s “Heroes” album, “Heroes” the song was clearly a high point of the fruitful Berlin sessions that saw Bowie finish up his Low album and helm Iggy Pop’s second solo album, Lust For Life. It was a tune from the latter that Bowie revisited for “Heroes”, using the simple two-chord progression of the Iggy song Success for the basis of “Heroes”’s dramatic slow build.

Sitting in with his rhythm section of guitarist Carlos Alomar, bassist George Murray and drummer Dennis Davis, Bowie pounded away at a grand piano while Brian Eno, his co-conspirator for what would become known as the “Berlin Trilogy” of albums, let fly with his EMS Synthi AKS synthesiser – a rudimentary piece of equipment responsible for creating a noise that seemed to envelope everything else in the room.

“He had an old synthesiser that fits into a briefcase made by a defunct company called EMS,” Tony Visconti later wrote on his website. “It didn’t have a piano keyboard like modern synths. It did have a lot of little knobs, a peg board and little pegs, like an old telephone switchboard, to connect the various parameters to one another. But it’s pièce de résistance was a little ‘joystick’ that you find on arcade games. He would pan that joystick around in circles and make the swirling sounds you heard on that track.”