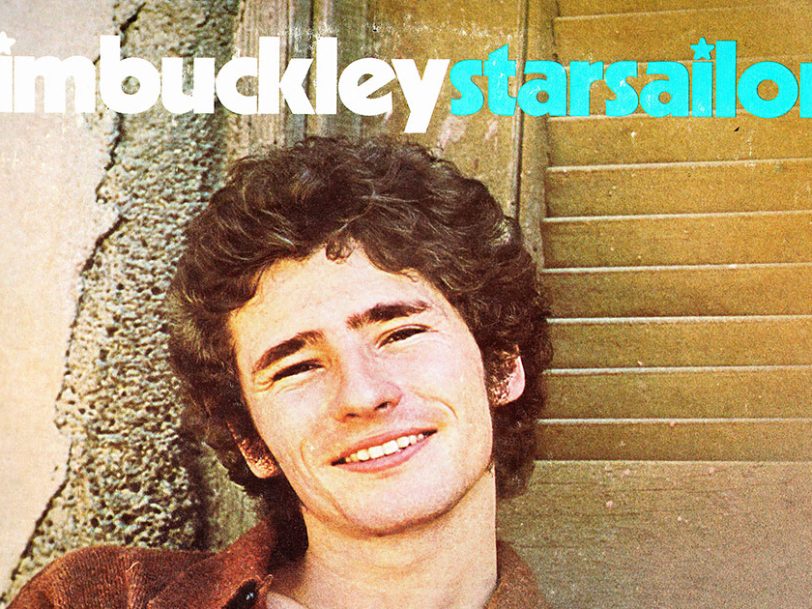

Released in November 1970, Tim Buckley’s fifth album, Starsailor, found the singer-songwriter embracing free jazz and experimental classical music to create a record like no other – not only in his body work, but in the whole of rock music. In casting aside the restrictions of conventional song structure and embracing the wild possibilities of his extraordinary vocal range, Buckley found his way to the purest expression of his talent and musical curiosity.

“For him to discover experimental classical music and then excel at it was no surprise”

Buckley’s second album of 1970, Starsailor capped a remarkable period of creativity for the singer-songwriter. In just over four years he’d transformed from the lovelorn folk-rock troubadour of his self-titled debut album to an expansive artist taking music to brave new places. The 12 months preceding the release of Starsailor alone produced the warm, melancholic Blue Afternoon and the eerie and experimental Lorca, two albums recorded simultaneously at Whitney Studios, in Glendale, California.

Yet Starsailor began with Buckley looking back. In early 1970 he called his old collaborator, the lyricist Larry Beckett. The pair had last worked together in 1967, on Buckley’s second album Goodbye And Hello, and, in the meantime, Beckett had been drafted into the US Army, going AWOL when it came time for him to be shipped to Vietnam (he eventually escaped the conflict on mental-health grounds). Buckley flew to Portland, Oregon, where Beckett was based, and together they wrote I Woke Up, based on Beckett’s feverish poem of the same name. More songs followed, including Monterey and Moulin Rouge. Starsailor was taking shape.

“A lot of conscious artistry was involved. Tim worked hard on every aspect”

Buckley had recently been devouring the work of modern avant-garde classical composers such as Luciano Berio, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Morton Subotnik, Olivier Messiaen and Krzysztof Penderecki. His adventurous listening habits chimed with Beckett’s own, as the lyricist recalled in an interview with Uncut in 2020. “I discovered things like Nirvana-Symphony by Toshiro Mayuzumi,” Beckett explained. “One day I said, ‘Tim, you should hear this, he’s turned the sound of a bell into a choir, with Buddhist chants going on in the background.’ He said, ‘If you have anything like that in your record collection, you’ve got to play it for me now!’ He was into every kind of music you could imagine. For him to discover experimental classical music and then excel at it was no surprise to me.”

Bassist John Balkin had joined Buckley for the recording of Lorca, and he would play a key role in helping the singer realise his latest musical ambitions. Balkin played in an experimental improv group called Menage A Trois, with brothers Bunk (alto flute, tenor saxophone) and Buzz (trumpet, flugelhorn) Gardner, formerly of Frank Zappa’s Mothers Of Invention. Following Lorca’s release, Buckley invited the trio on tour with him, adding former Janis Joplin drummer Maury Baker to the line-up.

Speaking to the San Diego Door in 1971, Buckley explained how the group came together: “John, Buzz, and Bunk, the two horn players and the bass player, have known each other since before WWII. They’ve done a lot of gigs together. They make tapes at home all the time; they have libraries upon libraries of what they do together on tape. They have a fantastic little studio in a very small place with fantastic little goodies and gadgets… I decided that I had to get myself together and really get into knowing what this stuff is all about and it’s been working out pretty good. That’s basically what it was. When Maury came along, everybody knew this drummer that played the timpani and somehow got around to us.”

“He was in complete command. It was astonishing”

The new group developed an understanding on tour, which blossomed when the Starsailor album sessions began on 10 September 1970, once more at Whitney Studios. Having reconnected with Larry Beckett, Buckley called upon another previous collaborator, guitarist Lee Underwood, who had played on every Buckley album so far. On visiting the studio, Underwood was surprised by Buckley’s confidence, later telling Uncut that the sessions were “markedly different” from how they used to be. “With Goodbye And Hello he’d wander around in the studio going, ‘I don’t know, what do you think we should do?’,” Underwood recalled. “For Starsailor, he was in complete command. It was astonishing.”

The guitarist further emphasised the control that Buckley had over his new music: “Tim spent a lot of time writing the lyrics, and even more time working with the odd time signatures and unusual melodic and harmonic factors as well. Improvisation is involved on Tim’s part and the other musicians’ parts as well, but a lot of conscious artistry was involved on Tim’s part before he and the musicians ever got into the studio. This was not a slap-dash ‘shot in the dark’ effort. Tim worked hard on every aspect of it.”

The tracks that comprise Starsailor aren’t so much songs as incantations of lust, ecstasy and oblivion. Opening track Come Here Woman is ushered in on waves of percussion and tense, fidgety guitar until the band settle into a loose groove, Buckley’s voice soaring magnificently. The jazzy ballad I Woke Up harks back to Buckley’s jazz-folk days in places; elsewhere it veers between fevered passages of improvisatory playing and moments of great beauty, courtesy of Buzz Gardner’s mournful trumpet solo. Monterey centres around a snaking guitar riff and clattering percussion, over which Buckley really lets rip vocally, from bluesy hollering to blood-curdling screams.

The pairing of Moulin Rouge and Song To The Siren sit apart from the rest of the album. The former is a jaunty cabaret number sung in French, written after Buckley told Beckett he’d always wanted to sing in the language. Song To The Siren, however, would become Buckley’s signature tune, a powerful ballad that had been written years previously and performed by Buckley on the final episode of The Monkees’ TV series. According to Beckett, Buckley retired the song not long after that, when singer Judy Henske made fun of one of its lyrics (“I’m as puzzled as the oyster”). Henske would later contradict the story, saying she liked the line.

Beckett revisited Song To The Siren for the Starsailor sessions, changing the lyric to “I’m as puzzled as the newborn”. After Buckley added the word “child”, one of the best Tim Buckley songs of all time was complete. While in its original form (best heard on the 2001 rarities compilation The Dream Belongs To Me: Rare And Unreleased Recordings 1968-1973) the song was a wistful gem reminiscent of early career highlight Once I Was, from 1969’s Happy Sad, on Starsailor it became an anguished torch song with layers of Buckley’s overdubbed, echoing wails adding to the sense of unease.

“His range was incredible”

Jungle Fire and Down By The Borderline open and close the second half of Starsailor with wild jazz-funk freakouts as Buckley works through his astonishing repertoire of vocal tricks. Elsewhere, the album’s near title track, Star Sailor, is the most far-out thing on the record – an a cappella piece with multiple Buckleys sped up, slowed down and warped beyond recognition. Speaking to Mojo in 1996, bassist John Balkin recalled the session that resulted in the song. “For the Star Sailor track itself, we wanted things like Timmy’s voice moving and circling the room, coming over the top like a horn section, like another instrument, not like five separate voices,” he explained. “His range was incredible. He could get down with the bass part and be up again in a split second.” The Healing Festival followed: an exhilarating, seat-of-your-pants free-jazz-inspired workout with more improbable vocal gymnastics from Buckley.

Starsailor should have been the first step of an exciting new chapter of Buckley’s career, but poor sales and a confused reception from the majority of critics stalled his progress. Few tapes survive from his subsequent live shows with the Starsailor band; those who were lucky enough to witness them say he pushed himself further than ever.

Initial plans to continue recording with the group were scrapped when Buckley felt he didn’t have the support of his record label. When he returned, in 1973, with the Greetings From LA album, Buckley had reinvented himself as a lusty funk-rocker – a much more straightforward proposition. For many, though, Starsailor is his mind-boggling, untameable masterpiece.

Find out what Starsailor tracks ranks among our best Tim Buckley songs.

More Like This

Why Cher’s Christmas Album Is Already A Modern Classic

Taking even its creator by surprise, Cher’s Christmas album is as traditional as it is unexpected, bearing the pop icon’s stamp throughout.

How Spandau Ballet’s Live Debut Launched The New Romantic Movement

With Christmas 1979 approaching, Spandau Ballet made their debut live show, igniting a pop revolution soon billed the New Romantic movement.

Be the first to know

Stay up-to-date with the latest music news, new releases, special offers and other discounts!